Fan art is everywhere...

From bustling stalls at Comic Con to the depths of Instagram feeds - yet it exists in a legal and moral grey zone. Should it be celebrated or is it theft? A way for artists to have fun putting their own spin and an existing character, or the pre-cursor to a corporate headache?

In this post I'll unpack the history, economics, and ethics behind fan art, and ask where that leaves creators who simply want to make a living!

What exactly is fan art?

Fan art is artwork (illustrations, paintings, sculptures or crafts) created by fans that depict characters, settings, or stories from someone else’s intellectual property (IP).

If I drew a picture of Spider-Man, Harry Potter, or Goku, this would of course be considered fan art.

Unlike licensed merchandise, fan art is almost always made without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. It can be purely for personal enjoyment, shared online for free, or sold through online stores or conventions.

A Personal Shift in Perspective

For years, I believed selling fan art was wrong. How could I, or any artist, justify profiting from someone else’s ideas and creative labour?

If you’re creatively inclined and love to draw, why not invent your own characters, design their outfits, and give them unique backstories or personalities? After all, making something that is original, unique, and personal to you is more fun anyway, right?

But over time, my view changed. I began to see that, for many artists trying to earn a living, creating fan art isn’t just a guilty pleasure - it can be a necessity. In a crowded market, drawing what people already love and having instant access to an existing audience of fans can be the difference between a thriving art career and abandoning the craft altogether.

I want to discuss why I’ve arrived at this conclusion, despite my initial feeling that fan art is uninspired, of low artistic value and that selling it is both morally wrong and completely illegal.

A Brief History of “Fan Art” Before Fandom

Long before comic conventions and online fandoms, artists made their living by re-imagining stories that belonged to the culture at large.

In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, most painters worked on church commissions, creating vivid images of biblical scenes and saints. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508–1512) is a towering example: a masterpiece built on narratives that every viewer already knew.

Likewise, thousands of Madonna and Child paintings circulated across Europe—not because the subject was original, but because it resonated deeply with the public and with paying patrons.

In that sense, these works functioned much like today’s fan art. The artists weren’t inventing their own intellectual property; they were visually interpreting a shared mythology for an eager audience.

You could also argue that, in terms of cultural reach, yesterday’s Holy Bible functioned a bit like today’s One Piece tankōbon (manga book). A story everyone knew and shared, even if the initial presentation was spiritual rather than recreational.

As printing spread in the 18th and 19th centuries, illustrators carried the tradition into new realms. Engravings for Grimm’s Fairy Tales or dramatic depictions of Shakespearean plays filled books and newspapers, giving classic folklore a fresh visual life. These creators were celebrated, not scolded, for bringing beloved stories to new audiences.

Before the word “fandom” existed, artists were already thriving by drawing the icons of their era - proof that the impulse to honour and reinterpret popular narratives is centuries old.

Modern Mythologies & the “Death of God”

When the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche declared in the 19th century that “God is dead,” he wasn’t celebrating atheism so much as observing a cultural shift: traditional religion was losing its central role in giving people meaning and moral direction. In the vacuum that followed, new kinds of myth-making stepped in.

Today, vast pop-culture universes provide many of the same functions that scripture once did. Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, the Marvel universe, Dragon Ball - each offers epic narratives of good and evil, loyalty and sacrifice, personal growth and cosmic stakes. Fans memorize lore the way medieval villagers memorized parables. Quoting Yoda or Gandalf can carry as much symbolic weight in some circles as a Bible verse once did.

Fan art is more than a passing gimmick. It becomes a kind of modern devotional practice. Events like Comic-Con are the pilgrimages; cosplay the ritual garb; and sharing art online is the digital equivalent of creating illuminated manuscripts. By drawing these beloved characters, artists participate in keeping the myths alive and relevant, not unlike Renaissance painters reimagining scenes from the Gospels of their time.

The Legal Landscape

The moment an artist creates an original drawing, painting, or digital piece, it’s automatically protected by copyright. In most countries that protection lasts for the life of the creator plus 70 years. When a work is produced as a “work for hire” (as is typical in film, animation, or comics owned by a studio), the term is even longer - 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter.

As an artist, I’m grateful that my work is legally protected and that the fruits of my labour can’t simply be stolen. In fact, this protection just recently allowed me to take legal action and be awarded settlement against a business owner who stole and used my Day-of-the-Dead artwork verbatim.

Large entertainment companies guard their properties fiercely. Disney is the most famous example: it successfully lobbied for the 1998 U.S. Copyright Term Extension Act - often nicknamed the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act” - which added 20 more years to the standard term, ensuring that early Mickey cartoons stayed under Disney’s control. I can appreciate Disney wanting to retain the rights to it's original cartoons since Mickey has always been synonymous with Walt Disney and the company.

However, when a large corporation hoards the rights to an IP that has grown to biblical proportions, this isn’t about protecting an original creator anymore. It’s about monopolising the original creation and exploiting its fandom to enrich distant shareholders. That’s something I take issue with.

Fan art exists squarely in a grey zone:

For personal use and sharing online, fan art is generally tolerated. A drawing posted on Instagram, hung in a bedroom, or used as a phone wallpaper rarely attracts legal action.

I wouldn’t put it past some unscrupulous corporation to one day try to monetise a child’s Pikachu fridge drawing, but thankfully, for now at least, policing this kind of use is virtually impossible.

Personally, I don’t mind if anyone creates fan art of my original creations, or even takes photos of my work, prints low-resolution versions, and displays them at home. And this is despite the fact that I make my living selling art prints- albeit high-resolution, signed editions on quality card stock.

At the end of the day, I’ve realised that not everyone can afford art. And with pretty pictures now virtually free thanks to AI tools, the true value of my work lies in the exclusivity of owning a signed edition and in supporting me (a real, individual human being!) as an artist to continue creating.

When it comes to selling fan art commercially, this is often technically considered an infringement on copyright. An example of merch containing someone else’s characters is typically considered illegal unless the artist has a license or the work clearly qualifies as fair use. For example, a transformative parody or commentary artwork can be argued to not break copyright.

Exactly at what point art is considered “transformative” for example is vague and subjective.

There have been a few headline-making clashes:

Lucasfilm v. Ainsworth (2011): A British prop maker selling replica Stormtrooper helmets faced a long legal battle. UK courts ultimately ruled in his favour because the helmets were classified as industrial design rather than art. A rare outcome and not a general precedent for fan artists.

Blizzard, the studio behind World of Warcraft, Overwatch, and other popular games, is famously protective of its intellectual property. Over the years, it has sent countless cease-and-desist letters to individuals and small businesses selling unlicensed merchandise - everything from T-shirts and posters to figurines featuring its characters.

Japanese doujinshi (fan-made manga) markets use a contrasting approach. Manga publishers often allow small-run fan comics to be sold at events like Comiket (a doujinshi convention), viewing them as free publicity and a way to nurture future professionals. An approach I whole heartedly agree with.

The most interesting case features the pop-artist Andy Warhol:

In the 1960s and beyond, his work frequently involved taking existing images - photographs, advertisements, or celebrity portraits, and transforming them into art. Famous examples include his Marilyn Diptych (1962) and his series of Campbell’s Soup Cans.

While some photographers and original image creators sued Warhol for copyright infringement, courts often sided with him.

The key reasoning: Warhol’s work was transformative. He wasn’t merely copying the original photographs; he reinterpreted them, changed context, and created something new with a distinct artistic expression. This distinction - between straight reproduction and transformative creation is central to the legal concept of fair use.

To reiterate: Warhol literally copied a trademarked soup can and sold the painting / prints for profit. He also took a photographer’s image, adapted it ever-so-slightly, and the courts still considered it legal. In the world of fine art, it seems you can repurpose copyrighted content with only minimal transformation.

These precedents are often cited in debates about fan art: if an artist can transform a character or image meaningfully, they may have some legal protection, but it’s risky, and commercial sales can still attract lawsuits.

Perhaps the video game equivalent of Warhol's example might be taking a World of Warcraft screenshot, printing it onto a huge canvas after adding a filter, and suddenly you have a “transformative” work of art. But, common sense tells me the legal system would side with Blizzard here.

Curiously, even if I pushed this example further, creating an existing Warcraft character with a completely unique style, pose, and colour palette - therefore transforming the original concept far more than Warhol ever did, and then sold it on a mouse mat on Amazon, I’d still likely be liable for copyright infringement. In other words, the same creative act is treated very differently depending on the medium and market.

Warhol’s victories highlight the tension at the heart of fan art law: copyright exists to protect creators, but transformative reinterpretation is sometimes recognized as legitimate artistic expression, even when it borrows heavily from existing material.

Economics and morality of IP Control

Franchises like Star Wars, Dragon Ball, and Pokémon aren’t just meaningful and beloved fictional worlds - they’re multi-billion-dollar machines. Corporations guard these properties fiercely because the financial stakes are enormous.

- Disney earned about $4.9 billion in 2024 from “Consumer Products & Licensing” alone.

- Bandai Namco pulls in over ¥120 billion (≈$800 million) each year from Dragon Ball merchandise.

- The Pokémon Company’s lifetime revenue has surpassed $90 billion from games and merchandise combined.

With numbers like these, it’s easy to see why corporations defend their IP empires so aggressively. Yet it raises a harder question: why should an independent artist selling a handful of prints be shut out of even a microscopic share of this enormous cultural and economic pie?

Many fandoms today hold as much meaning for their communities as ancient myths or religious stories once did. But unlike those shared cultural stories, modern pop-culture fictions are locked inside corporate portfolios. A multinational conglomerate, often run by executives far removed from the art itself, now decide who may create or profit from these worlds, not for cultural stewardship, but simply to maximise revenue.

Historically, artists painted saints, deities, and epic heroes without needing a license. Now, when our spiritual and narrative touchstones are company assets, creative expression and a means for artists to generate income is constrained. Telling artists to “just sell original work” ignores a market dominated by well-funded franchises that command attention, nostalgia, and marketing budgets individual creators can’t match.

Artists bring imagination, skill, and cultural value that exceed cold corporate interests. Yet when meaning-rich universes are treated purely as assets, the very people capable of birthing the next great mythology are left with fewer ways to sustain themselves.

The Case for Fan Art

Fan art is becoming a vital part of today’s creative ecosystem.

It’s a gateway for emerging artists - Reimagining well-known characters attracts attention and helps new artists build audiences that later discover their original work.

It’s part of community building - Fan art reinforces shared enthusiasm and keeps franchises vibrant long after official releases fade. For this reason, some companies recognise the fandom surrounding their IP and actively promote it. In the case of fans then selling the occasional fan art print, they might even avoid interfering in order to appear as though they aren’t some bullying tyrant, going after the little guy and causing backlash within the fandom community.

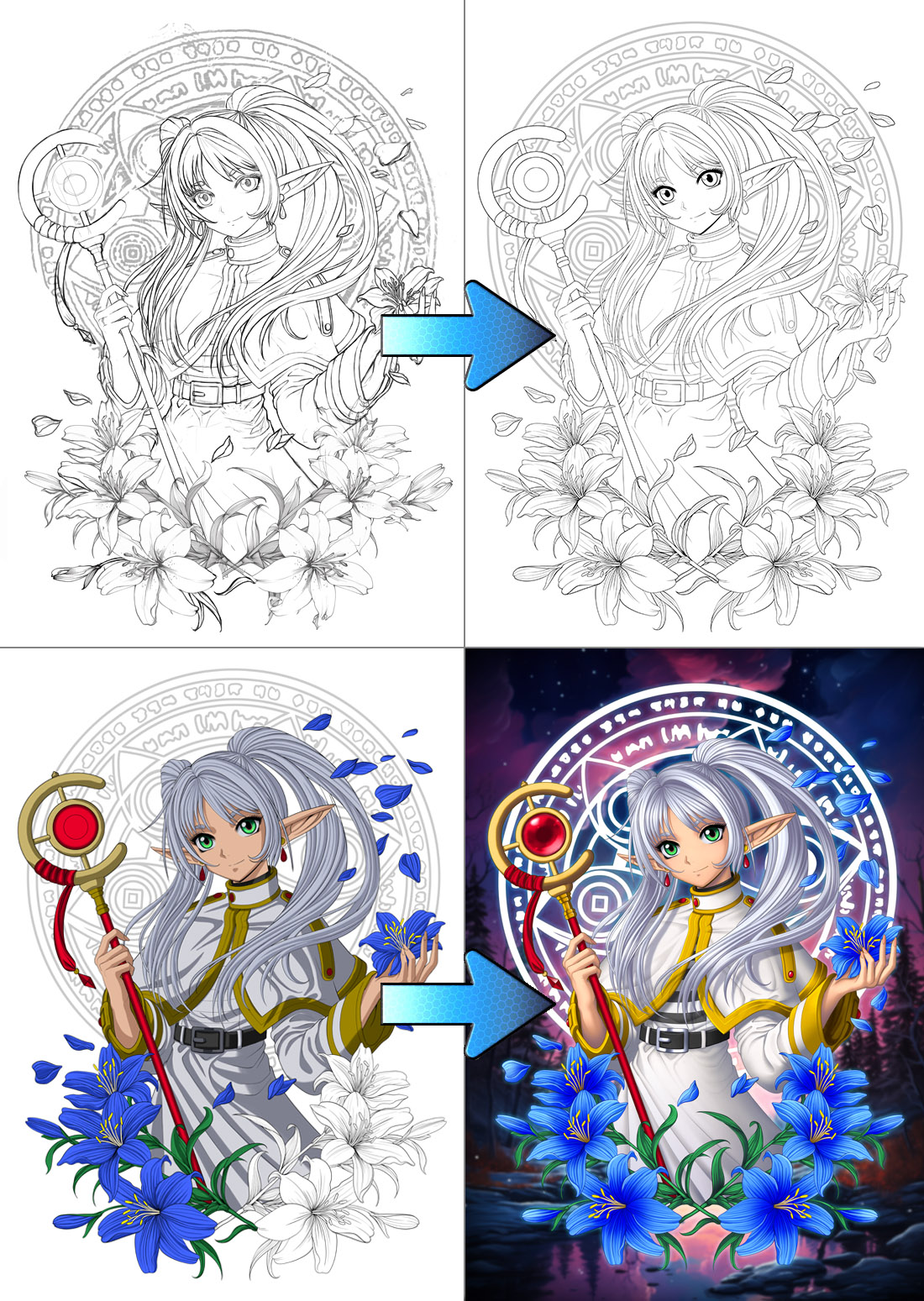

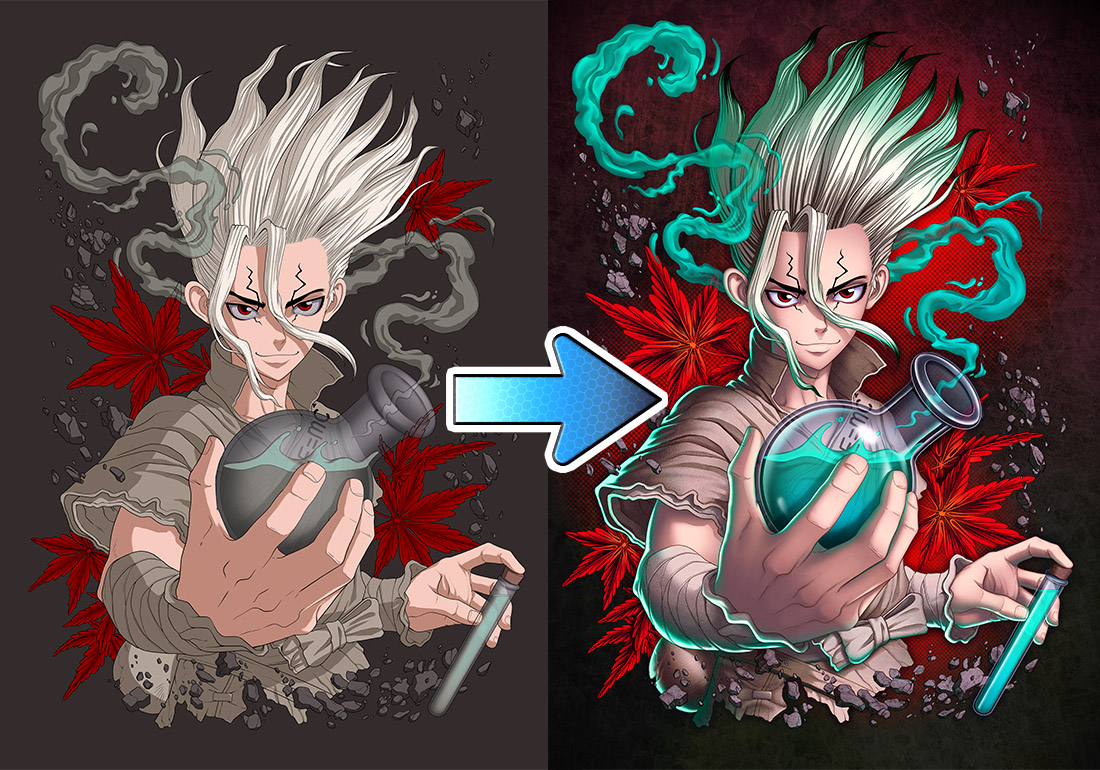

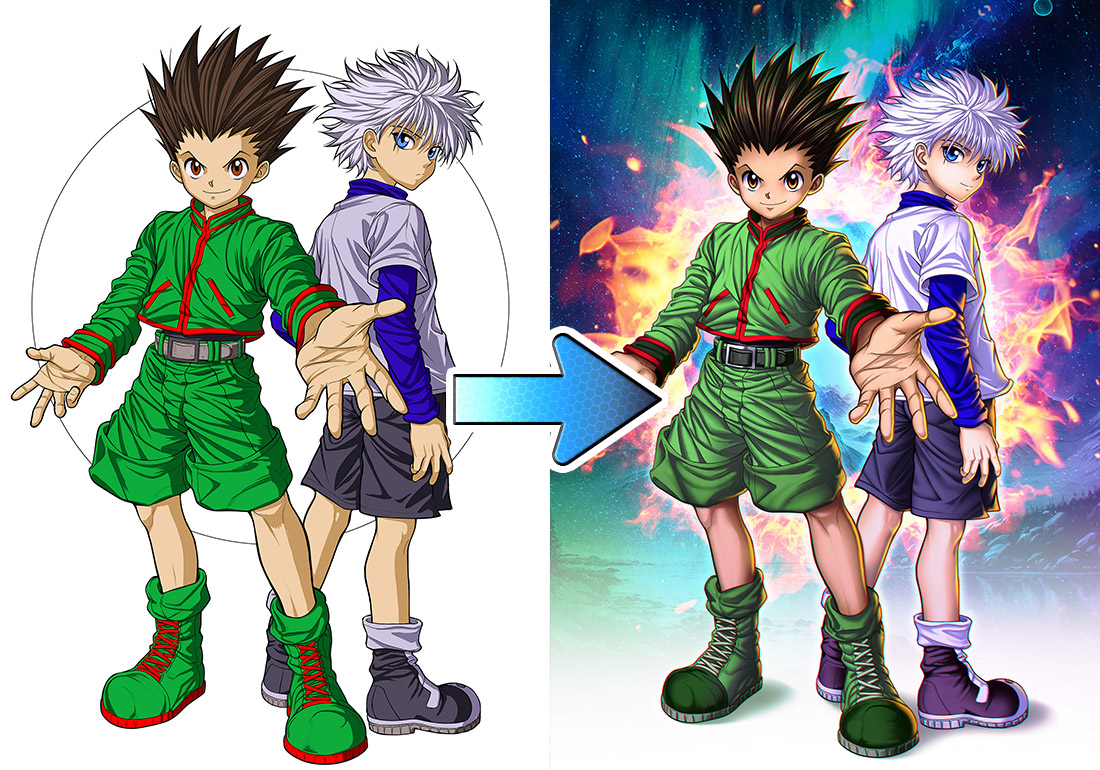

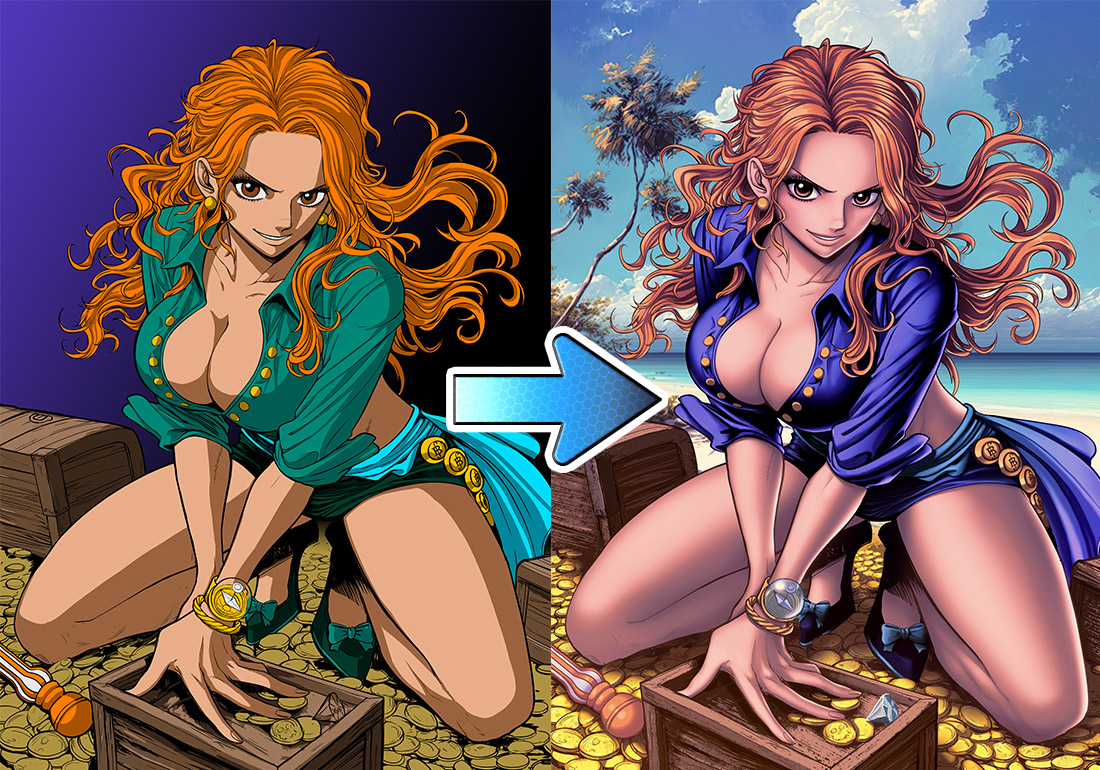

It creates a point of cultural conversation. Transformative pieces - gender-swaps, mash-ups, stylistic reinterpretations and so on all add fresh meaning and can stand as original art in their own right.

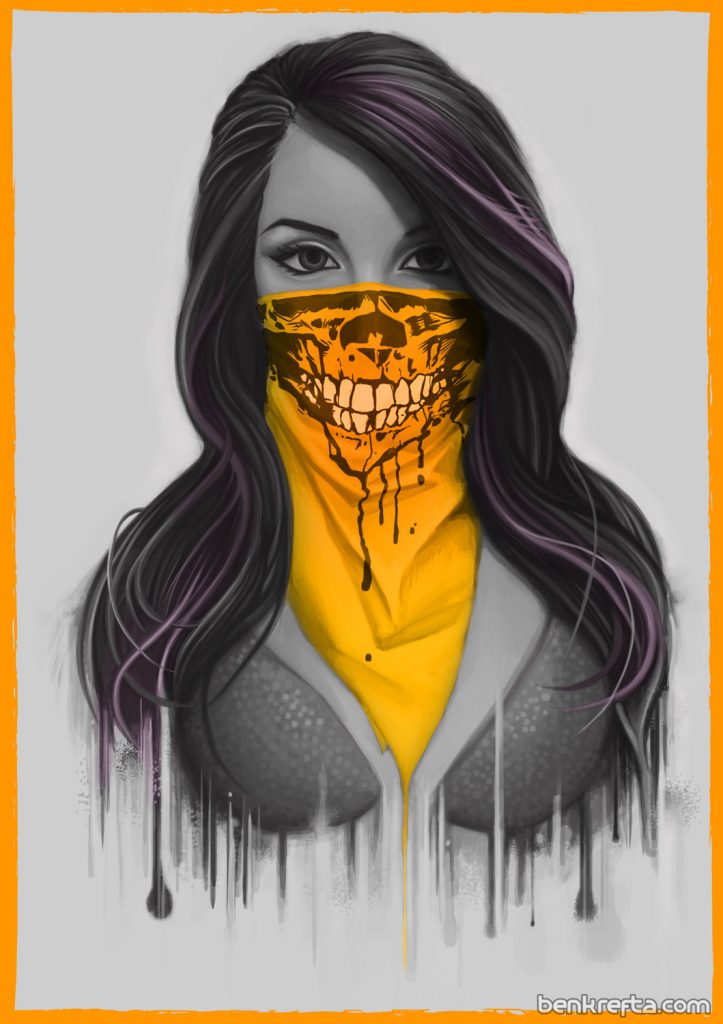

Many professional creators quietly welcome it. Game publishers have been known to buy fan art prints of their game at conventions and manga ka (the original artists) post fan art tributes to their creation to social media. This is great. It helps provide artists the opportunity to monetise their talents. sustain a living and finally cash-in on the thousands of hours practicing their craft. The problem with individual artists selling fan art often occurs once a company becomes large, and super invested enough in their guarding their acquired property at all costs.

Fan art, in other words, is less a legal nuisance than a living dialogue between fans and the worlds they love.

The Case Against Fan Art

At the end of the day, commodification of a creative idea or work now exists. The ability to sell one’s idea or creation to a larger company can benefit the original artist and founder. And even be the difference between them making a living or not.

Selling prints or merchandise of another company’s characters without a license is, by definition, a copyright violation. Without any legal protections, it would be difficult for anybody to create anything new, for fear of it being ripped off the next day.

Sometimes fan art can overshadow the artists who are focused on their originals. If online marketplaces are overflowing with fan art, this makes it harder for the artists with fully original creations to stand out or earn a living. Surely, they deserve customers without needing to piggy-back off existing fandoms?

Brand dilution and offensive uses - Rights holders fear their characters could be associated with low-quality work, explicit content, or messages that damage the brand.

From a company’s perspective, tight control protects both revenue and reputation. Even if they quietly tolerate small-scale fan art sales, they reserve the legal right to act when a fan creation crosses the line.

Where This Leaves Artists

For working artists, the fan art landscape is equal parts opportunity and legal hazard. Here are some practical, non-legal tips to navigate it:

Go “inspired by” or parodic: Create pieces clearly transformative: unique style, new composition, or commentary. Parody and satire can qualify as fair use in some regions.

Keep it small and local: Limited-run prints at conventions or direct commissions are less likely to draw legal fire than mass-produced online merch.

Blend with public domain: Mash-ups with classic myths, folklore, or works whose copyrights have expired (Shakespeare, Greek myths) to add originality while sidestepping claims.

Use fan art as a funnel: Draw beloved characters to attract attention, but always showcase and promote your own original IP alongside them.

Final Thoughts

Fan art is both homage and potential infringement.

It keeps beloved mythologies alive, yet it also shows how extended copyright terms can stifle creativity.

Artists walk a tightrope: without fan art, fewer creators might never build an audience or sustain a living; without copyright, corporations fear lost revenue.

Personally, I value copyright for safeguarding inventors and original creators from outright theft. But it’s hard to care about corporate profits or the wealthy investors who over-commodify and monopolise fandoms. I understand a company protecting its assets from direct competitors. Yet when big corporations crack down on individual fan artists - people offering fresh, imaginative takes on beloved characters - it rarely feels just. After all, without artists there would be no fan-favourite properties to protect, so why target the very creative class that built them?

The vast majority of aspiring professional artists are not wealthy, nor are they in it for the financial reward. Greed or power is not the incentive. Rather, they want the opportunity to engage in their passions, to bring creative and aesthetic value into the world. Some want to create fan art for the love of it, others as a means to survive by utilising their unique set of skills. Perhaps I'm just speaking for myself here? But either way, we shouldn't be so quick to criticise and condemn those who create an original take on existing characters, or attempt to earn a living.

Transformative work isn't morally wrong and not even illegal in the correct context.

It’s crucial to distinguish between transformative fan art and outright image theft. That is to say, new creations built from the ground up with a unique vision, talent and skill; compared to stealing (or direct copying) and selling someone else’s art /image.

Transformative work enriches culture, builds upon and clearly differentiates itself from the source; piracy does not.

Unfortunately, online copyright infringement bots and licensing agents scouring the internet for offenders rarely care about that difference.

Much like the courts which eventually ruled that Warhol’s paintings and prints were transformative artworks in their own right, thoughtful fan art deserves the same recognition. As long as it’s clearly distinct, not traced, and not a direct reproduction.

Still, selling fan art always carries legal risk.

The most common outcome is simply a takedown notice, but there’s always a chance of being sued for damages and legal costs, which can become a stressful and expensive ordeal.

Perhaps legal enforcement should be somewhat nuanced and rank in severity depending on the crime:

- Blatant piracy and theft,

- Direct reproductions,

- Cheaply produced AI generated content,

- Slightly modified works (like adding filters),

- And only then, transformative art if you insist on going after the independent, starving artists and fans!

Strangely, I've noticed fan art often gets flagged for infringement before direct theft. The uniqueness of the fan art stands out. Where as Bootleg sellers routinely peddle what, at first glance, appears to be non-modified, licensed art, and copyright agents often assume (wrongly) that a licence exists. Or the seller simply lies about having one. In reality, it would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to legitimately purchase a range of licences, and it’s absurd to think a small Etsy shop selling low-resolution, poor-quality T-shirts for example has paid for them.

Even if we don’t consider fan art transformative, perhaps a solution for selling it would be to offer artists an affordable, streamlined licensing model or profit-sharing system. An agreement that allows independent talented creators to contribute to the franchises and fictional worlds they love without fear of takedowns, while rights holders still receive their share.

It would make more sense for a company to gain a modest cut -say 10 % of each sale, than to pay out money hiring agents to issue takedown requests, where ultimately no one benefits.

Lastly- the take home question to consider:

I hope this gives a little more nuance to the issues surrounding fan art.

If you’re wondering, “should I create a business to sell fan art?”, the answer is no.

Firstly, you should always respect the law locally, or international. Secondly, despite arguments made for fan art potentially sitting in a legal grey area, dealing with any potential legal proceedings is not worth the hassle. You might be morally justified and even legally justified in some courts, but often the companies pursuing action against artists are mega corporations that have unlimited legal budgets. You do not. You or your lawyer will likely be unable to compete with theirs.

However, personally I believe certain fictional fandoms have become a huge part of modern culture. For some, they carry a depth of meaning and significance which has, to some extent, outgrown the idea of them simply being an entertainment commodity to capitalise on and profit from.

Therefore, is it right the a for a multi-trillion-dollar fortune 500 company to buy up everyone’s favourite IPs, monopolise them and exploit devoted fans to increase profits?

And in turn, should the artist class be constantly put on the chopping block for creating art that may or may not be considered ‘transformative’?

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts